The Lean Startup - Book Summary

Most new businesses/products fail. The Lean Startup is about how to increase the chances of success by learning what our customers really want, as quickly as possible.

The book was written by Eric Ries, who used Lean Startup principles to grow his company (IMVU) from a fledgling startup to a business with a $50 million annual turnover.

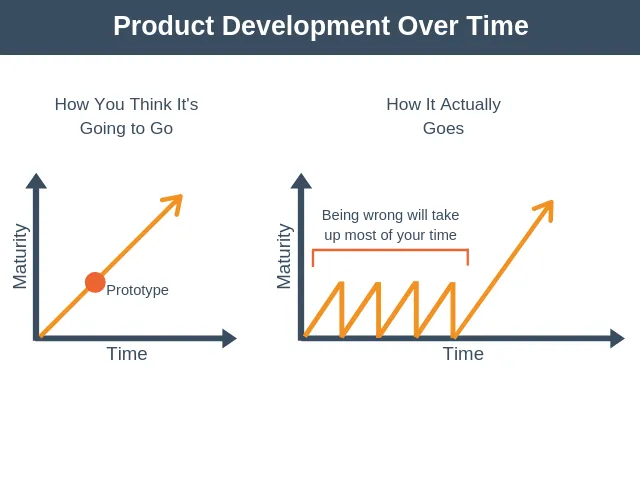

Much like learning a new skill, product development is not a linear process, as suggested by the below image.

We should be comfortable with failure and starting again with our new learnings. The faster we fail, the faster we learn.

The book is broken down into 3 sections.

- Vision: Explains what an entrepreneur is in the context of this book and how startups experiement to learn as quickly as possible

- Steer: Covers most of the build-measure-learn feedback loop, when to pivot and how to pivot

- Accelerate: Covers how to progress through the build-measure-learn while scaling once you've discovered the product that you want to make a sustainable business

Entrepreneurs, for the sake of the book and this summary is not limited to startup founders but includes people in large organisations too.

The job of an entrepreneur is to learn what your customers want in a way that you can build a sustainable business. This learning is to be conducted as scientific as possible.

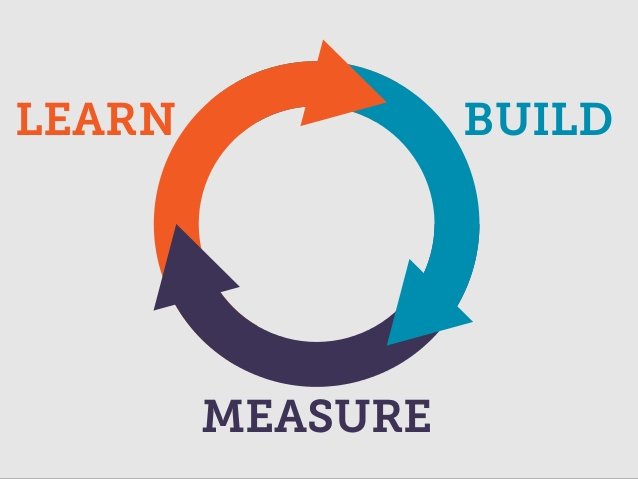

The main principles and techniques outlined in the book to achieve this is the Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop and innovation accounting.

The goal of this process is to learn as quick as possible and shorten the time through this feedback loop.

The way we do this is by starting with a hypothesis, building a minimum viable product (MVP), which allows us to reliably test this hypothesis and then measuring the results.

Then we answer the following questions to find out what we learned

- Was your hypothesis correct?

- If it was off, by how much?

- What have we learned?

- Do we need to change an element of the strategy? Or even the entire strategy?

The faster we move through this loop, the faster we learn. If we can create 10 or 100 prototypes in 200 days, each with improvements in some way based on what we learned from customers, we learn so much more than if we build one fully functioning product in a silo, this is how we can figure out what customers really want.

Types of Hypothesis

There are two types of hypothesis outlined in the book

- Value hypothesis: what do your customers want.

- Growth hypothesis: how will your startup grow.

It’s important to test your riskiest assumptions first. These usually include:

- Do customers actually want what you’re planning to offer?

- Are customers willing to pay for it?

The reason we use MVP's to test this as opposed to just polling people, is that it's very common that if you ask someone "hey, would you buy this thing?", often they will say yes, but then if you ask them to get their wallet out and actually buy it, they decide they don't actually want to buy it.

This way we can test hypothesis using actual customer behaviour, not just opinions.

Types of Minimal Viable Product (MVP)

1. The Video MVP

Before actually building a product, you can fabricate a video of how the product will actually function once it's built, show the video to prospective customers and see if you can get them to pre-order it, usually enticing them with a discount

Video MVP Example:

The most famous example of the video MVP is by Dropbox. Dropbox founder, Drew Housten, used this 4-minute video to explain a complex product and receive positive feedback and some funds for development.

2. The Concierge MVP

This is based on the idea that when starting out you don't need thousands of customers, but you can refine the product by keeping just one special customer happy. You can service this one customer manually to prove the point about your service, before making it scalable.

Concierge MVP Example:

Food on the Table is a company that creates weekly grocery lists and recipes based on what you and your family like to eat.

It’s a complicated process, but when this business started, they had no technology and just a single customer that they gave the concierge treatment too.

Instead of interacting with software, that first customer got a visit from the CEO each week. He would review what was on sale at her preferred store and then create recipes based on this and her preferences. She would then be given the recipes each week in person and asked for feedback.

Although they had no product, nor were they building one, each week they were learning more about how to make their product a success. The team continued to add manual customers until they couldn’t handle and more. At this point, they started to work on their product.

3. The Wizard of Oz MVP

This is when you have a pretend product that customers believe they are interacting with the technology, but secretly there's a human behind the scenes doing the work.

Wizard of Oz MVP Example:

An example of this type of MVP was executed by Zappos.com. They challenged the conventional wisdom that people wouldn't want to buy shoes online as they would want to try them on first.

Nick Swinmurn, Zappos founder, decided to test his hypothesis that people actually would buy shoes online. To do this, he took photos of shoes and built a simple site selling them. When a customer purchased a pair, he went back to the store and bought them at retail price and then mailed them to the customer himself.

Before long, Swinmurn couldn’t keep up with demand. Thus Zappos was able to prove that people would buy shoes online, but they didn’t have to build warehouses, supply chains, stock management systems to prove it.

4. Other Types of MVP

There are many more ways to test your product that you could come up with, but here are two of the more common types.

Landing Page MVP

This is literally just building a landing page for your product with an option to purchase. This gives you an idea of how many people would be interested to purchase your product.

The key thing to remember with a Landing Page MVP is that you can use it to test whether customers want to buy your product without having to build any of your product.

Crowdfunding MVP

Using crowdfunding platforms to validate your idea and receive payment to fund the product before you've built it.

Examples of super successful crowdfunding campaigns include the Pebble smartwatch and a card game called Exploding Kittens. Interestingly, a simple card game about exploding kittens managed to raise over $8 million.

Launch as quickly as possible

Whatever kind of MVP you choose to use, the most important thing is to build the smallest possible product to test your hypothesis. Don't worry about it being too simple or the idea being stolen.

Measure

Traditional methods of measuring success in business, while perhaps useful for sustaining established products, are not helpful when it comes to new innovative products.

The book describes using metrics such as the total number of anything (users, sales, etc.) as lousy metrics. Eric called these "vanity metrics" as they are only useful to sound good but do not actually give us the useful information we are after.

Useful Metrics should follow the three A's

- Actionable: Your metric must show clear cause and effect. If you perform an experiment, you must understand how that experiment affected your metric. Otherwise, how will you know if you’re making progress?

- Accessible: Make your metric as simple for everyone in the company to understand as possible. For example, not everyone understands what a website “hit” is, but everyone knows what a person who visited your site means. Consider putting key metrics on public display screens so everyone can see them.

- Auditable: It should be possible to dig into the data to see how a particular metric is put together. This stops employees arguing about how the metric was constructed and allows people to focus on making progress.

Here are some specific metrics that are useful for measuring success in The Lean Startup

- Registration rate %

- Activation rate %

- Referral Rate %

- Lifetime Value (LTV)

- Customer Acquisition Cost (CPA)

- Net Promoter Score (NPS)

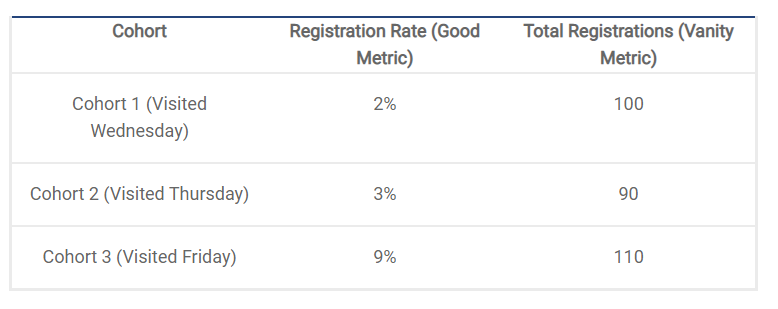

An excellent way to measure progress is by looking at cohorts. A cohort is simply a group that shares the same characteristic. Here is an example

Judging by this - you can see that the changes on Friday have increased the registration rate from 3% to 9%. If you look at total registration, you would not spot this improvement.

It's important to consider if there is anything special about Friday in particular that makes users more likely to sign up. Maybe they've got that Friday feeling. To overcome this problem, we can use A/B testing.

A/B Testing

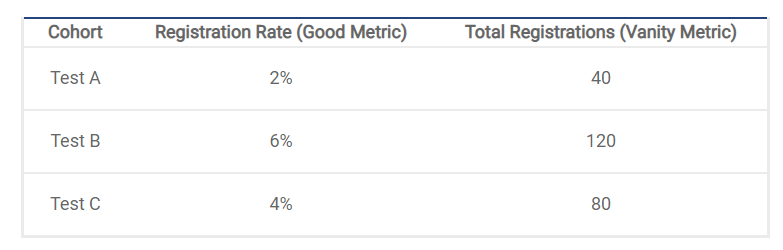

Also known as split testing, this is about showing users two or more versions of the webpage/product at random and measuring the difference in results. A/B testing gives us real quantatative data.

Here is how an A/B test might look

You can see that there are similar volumes of users registering and that Test B was the best performing.

The Pivot

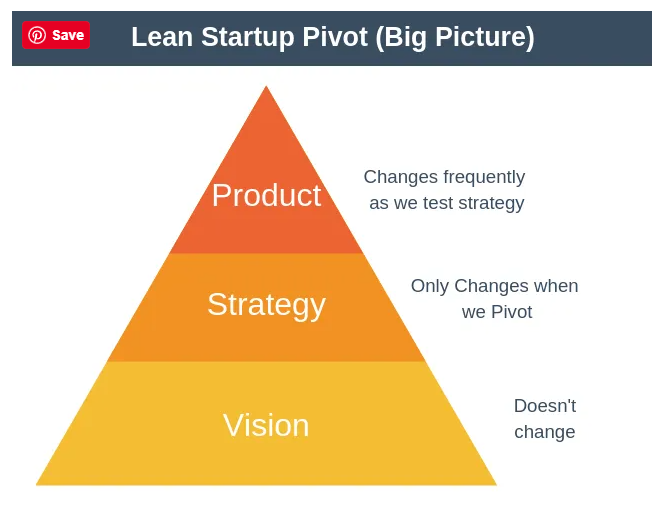

In the Lean Startup, we may find our progress plateaus and we need to pivot. We need to stay true to our vision, but change strategy.

To build a thriving business, you will need a clear vision. You also need a strategy to realize your vision, consisting of business model, product plan, and customers.

For example, Instagram found their social check-in app was actually mostly used for photo sharing? They decided to focus on and do that one thing well.

Or Pinterest who found that nobody was using their mobile app for shopping. But they did discover that they were creating and sharing wish lists.

When to Pivot

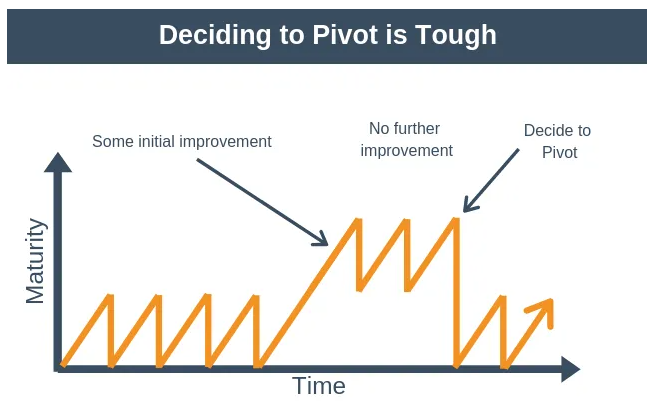

Deciding to pivot is a tough decision. One reason for this is that startups seldom encounter total failure when they test an idea. You may feel like your startup is chugging along but not really gaining any real traction.

The number one sign that you need to pivot is that your metrics aren’t good enough and that your experiments aren’t making any progress moving the needle.

When you find you've hit a plateau, it is common to be optimistic and think that the next experiment will move the needle. In this situation it's important to discuss to persevere or pivot.

In the above diagram you can see that the new experiments were not improving the key metrics, which suggests this is the right time to pivot.

Types of Pivot

- Zoom-In Pivot: Users really like a specific feature of your product. You decide to focus exclusively on this feature and drop all the others.

2. Zoom-Out Pivot: Your features aren’t enough on their own for customers, so you add more.

3. Customer Segment Pivot: Your product is great, but it’s solving a problem for the wrong group of users. You decide to pivot to a new target audience.

4. Customer Need Pivot: You’ve spent time understanding your customers, but the product you’ve built doesn’t solve a significant problem they have. You pivot to address a more important problem for the same customers.

5. Platform Pivot: A platform pivot involves changing from an application into a platform or vice versa.

6. Business Architecture Pivot: Here you pivot from a high margin and low volume sales approach to a low margin and high volume approach or vice versa.

7. Value Capture Pivot: In this pivot, you change the way you monetize your product. For example, you might move from an advertising model to a subscription model.

8. Engine of Growth Pivot: In this pivot, you change the way you attract customers. For example, you may move from an organic model to a paid model.

9. Channel Pivot: A channel pivot involves changing how you deliver your product to your customers. For example, you could pivot from selling directly to selling through third-party distributors.

10. Technology Pivot: A technology pivot happens when a company discovers how to deliver the same solution via a different technology, usually to save costs. For example, Netflix switched from providing CDs via the mail to delivering movies solely over the internet.

Accelerate

At this stage of the lean startup process we have figured out what product we want to build a sustainable business with.

Types of Growth Engine

- Sticky Growth Engine: When you acquire a new customer, you want them to stick around as long as possible. This is especially important for subscription services, social networks, and marketplaces. Churn rate is a crucial metric for these types of businesses.

- Viral Growth Engine: Relying on existing/new customers to bring in more customers. If each customer brings in enough new customers, then this can lead to exponential growth. Viral coefficient is a key metric for these types of businesses.

- Paid Growth Engine: This is by paying to acquire new customers, using ads for example. If a new customer generates more than it costs to acquire that customer, then you can use the excess profit to run more ads generating further profit. Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and Lifetime Value (LTV) are critical metrics for these types of businesses.

How to Avoid Growth Pains

Concept 1: Small Batch Sizes: This basically means to keep your updates small and release often, rather than releasing big batches at once. This reduces risk.

Techniques to help you reduce your batch size include:

- Adopt an agile methodology.

- Use automation to speed up your time through the Lean Startup loop, for example, automated testing.

- Find faster ways to prototype, for instance, by using continuous deployment, 3rd party software or 3D printers.

- Use a large screen to display critical KPIs in real-time to the whole team. That way, if something goes wrong, everyone will know about it straight away.

Concept 2: The 5 Whys and Proportional Investment: Growing startups tend to face conflicting tensions. Do you grow fast but scrappy or slow and steady? Do you hack and stub your product or do you build with quality in mind?

To find the root cause of the issue (which usually ends up revealing itself as a human problem rather than a technical problem) we use the 5 whys, which means we ask why 5 times.

To fix the problem we use the proportional investment technique

The 5 Whys

Ask why five times to get to the root of any problem. Example:

- Why did we get no new subscribers yesterday? Because the signup page was broken.

- Why was the signup page broken? Because it wasn’t connecting to the email database.

- Why? Because it was trying to access the old database.

- Why? Because the switch wasn’t something we tested.

- Why? Because the engineer didn’t realize a new database was being used.

By asking questions in this way, you get to the root cause of the problem. If you’d only asked two whys, you’d think that the cause of the problem was something entirely different.

In our example above it would only take a short time to fix. The engineer needs to be made aware of all new systems. Also, people introducing new systems need to talk it through with engineering. You could also add tests to ensure it doesn’t happen again.

But what about a more significant problem? Here you can be proportionate with your investment by understanding the cost of the problem and the cost of the fix. For example, an issue that occurs every week and costs $1,000 will cost $52,000 in a year. If it will cost $10,000 upfront to fix the problem permanently, then it’s worth fixing. However, if it’s going to cost $400,000 to fix, then it’s not.